This is the fourth installment of New Gamemaster Month!

In New Gamemaster Month we’re helping players who feel the urge to run an RPG—to become a GM for the first time—take the plunge. If you’re just joining us, start with the first installment. Then join us every Tuesday and Thursday throughout January, and by the end of the month you’ll be a GM too!

On Tuesday, we started digging into the rules and setting of our games. Developing a basic fluency in these topics—without sweating the details too much—gives you a foundation for keeping your game sessions flowing at a brisk and enjoyable pace, and allows you to form and run with your creative ideas and those of your players without the distraction of wrestling with unfamiliar rules.

So if that’s the foundation, what do we build upon it? The adventure, of course!

What Is an Adventure, Really?

An RPG adventure is a planned series of events that give a backbone to the story you, and especially your players, will unfold around the gaming table. As you develop your skill and experience as a GM, you might take great pleasure in crafting your own adventures. Or you might prefer to save yourself the effort and use the many fun and imaginative adventures already created for your convenience. Many GMs do both—they run published adventures when they have little prep time or are particularly inspired by the adventures’ ideas, and they make their own when they have the time and inspiration to do so.

Creating your own adventures isn’t hard. The amount of work required varies from game system to game system, but generally isn’t insurmountable. It’s a slightly different skill set than GMing in general, though, so it’s outside the scope of the New Gamemaster Month program. We’re going to go with a published adventure, to focus on the actual GMing process rather than the design process.

Before you flip open your adventure, let’s talk a bit about what an adventure consists of. Adventures can be highly detailed, or amount to little more than a few notes, but they all have a few things in common:

- An initial set of circumstances (an isolated village in the wilderness; a caravan encountered on the road; a treasure map that suggests a trip into the mountains). Often, a published adventure will offer a variety of “hooks” for involving player characters (suggestions for why they might come across that isolated village in the wilderness, for example).

- A conflict that compels the players to become involved (villagers have recently been disappearing; the caravan driver offers a big reward to help fend off local marauders; the treasure map hints at great riches).

- An outline of how the adventure’s story is likely to unfold. Sometimes the outline is very linear (event A leads to event B, which leads to event C). Sometimes the outline is “squishier,” with few or no assumptions about the order of events. And sometimes the outline takes the form of a map: The classic D&D dungeon is basically an adventure outline, with the passages and tunnels indicating how the events might connect to each other. The outline might be drawn out like a flow chart (or, again, take the form of a map), or it might just be a list of encounter descriptions. That takes us to:

- A set of encounters, or scenes. An encounter is a point at which something happens, and, typically, where the characters learn or gain something that moves their story forward. Encounters might involve combat, or a trap, or social interaction, a period of exploration, or some sort of environmental challenge.

- Finally, an adventure contains details on creatures, characters, and items the player characters will interact with during their encounters. This might include stats for creatures, descriptions about personality, appearance, and motivation for non-player characters, maps of adventure areas, lists of “loot” and other interesting in-game items the characters interact with, and illustrations of places, characters, or events.

Those are the components of any complete adventure. They might take the form of a 96-page book with thousands of words of detail, along with dozens of maps and images. Or they might amount to a few scribbled notes on a sheet of paper. Either way can suit the purpose just fine.

So if those are the basic ingredients, what does it take to make a really tasty meal out of them? A great adventure:

- Often has an element of mystery, or even a plot twist somewhere in the middle. That initial conflict was compelling, but it turned out to be just the tip of the iceberg!

- Has some element of story—often a very strong narrative—but doesn’t rely on or expect a specific course of action from the players.

- Usually has a variety of activities in it: Fighting, negotiating, exploring, working out puzzles or mysteries.

- But also plays to the interests of the players and the strengths of the characters. Players who love fast-paced action may become bored by an adventure that’s heavily focused on intrigue and social interaction. And a character that’s great at climbing, crawling, and sneaking around won’t get a chance to shine in an adventure that’s a series of straight-up combat scenes.

Running Your First Game Virtually

If you’re used to sitting in the same room with your friends, you may find that a virtual game creates a sort of “invisible barrier” between the participants. A distraction for one person (a TV on in the next room, for example) isn’t a distraction for everyone else. You’re all sitting in front of computers, so someone checks email. Or scrolls through Instagram. The technology gives the illusion of proximity, but there’s still a psychological distance between everyone. The invisible barrier is unique to online play, but there are a few steps you can take to reduce its effect.

The first step to overcoming the invisible barrier is recognizing that it’s there and that it affects players differently. The person in the later time zone sitting in the dark starts to get sleepy. The person who’s more prone to distraction has greater opportunity to let their mind wander. Players who otherwise would be attentive if they were sitting among their friends find that they can’t sit alone in a room doing nothing while someone else takes a turn, so they start scrolling through social media.

It’s a bit trickier to keep everyone engaged in the digital environment. So if someone’s quiet, address them specifically and ask what they think, what they plan to do, or something of that nature. Make sure everyone interacts at least once every few minutes of play.

This isn’t just the GM’s problem to solve, by the way. Remind your players about the invisible barrier at the beginning of the game, and ask them to be mindful not just of their own engagement, but also that of the other players.

It’s time to get to the specifics of your first adventure as a GM.

A Little Reading

Read Taker of Sorrow, on pages 363-375.

A Little Thinking

As you read it, think about the elements discussed above—both the fundamental building blocks, and the factors that make an adventure fun and successful. See if you recognize those elements in the adventure. Maybe you’d like to hop into the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group and talk about them with experienced GMs and other folk, like you, who are exploring GMing for the first time.

And a Little Talking

But that’s not your only activity. As mentioned above, an adventure works best if it plays to the interests and expectations of the players. So have a chat with them. Ask them what they expect and want out of the game. Some players will be happy to go on at length. Others might not really know what they want, or be able to articulate it. In some cases, you may have gamed with the player before, and perhaps already have a good sense of his or her play style. That’s all fine. The goal here is to put yourself in a position in which you can best prepare for a game that everyone will find memorable.

Don’t press your players on this—many gamers don’t really care to think about a game too much before they sit down at the table with a character sheet in front of them. But if you have players who are eager to think ahead about the game to come, you might tell them about shin obligation, and share some of the personal hooks, and other reasons to be involved in the adventure, given on page 365. And of course they aren’t limited to talking to you—they’re welcome to discuss their character ideas with one another beforehand, too.

Let us know how it goes in the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group. And talk to you again on Tuesday!

An adventure works best when players and GMs are interested in it. That’s why Unknown Armies starts with a collaborative effort. Working together helps everyone buy in to the premise and get excited about the games you’ll run. As an added benefit, it takes some of the responsibility off your shoulders.

Making Objectives

Why are the characters in your game going through trouble and conflict instead of sitting back and binging some Netflix show? In some RPGs, it’s because the characters are heroes. Not so in this game. In Unknown Armies, the players’ characters really, really, REALLY want… something.

That something is called the objective. It’s what the characters will go through hell to achieve. It could be noble (“Find out what’s kidnapping children and stop it”) or selfish (“Take over our hometown and rule it like capricious warlords”), but it’s something you’ll create with the players. Everyone should agree what their characters will be working towards. It also helps you know what kind of adventures to create. And since this objective will get a percentile ranking, it also tells everyone how close they are to achieving it.

Before the first session, read pages 13-22 in Book Two: Run. These discuss the finer points of creating objectives and offer some good advice to help make sure whatever your group creates will work for the game.

Having a clear objective makes your job easier. You know where their characters start and where they want to end up. You just need to fill in the details in between. In other words, the hardest part of creating adventures is knowing where to start — and that’s done with help by the players.

Heading Down That Path

Once an objective is created, you need to work together on a path. This is a series of milestones — ways to know the group is moving towards the objective. Think of them as mini-objectives so players feel like they’re getting somewhere. Line them up sequentially, and you have your plot!

By working together on the path and its milestones, you make sure your players are into the game. You also make sure that you don’t get overwhelmed with the work. You get an idea of what encounters and scenes to create for the players by knowing what lies on the path to the objective.

This is part of what makes running Unknown Armies so much fun. Because everyone had a hand in creating the objective and path, they don’t have to be sold on the plot. If they hate the idea of rescuing a princess, they don’t ever have to do it.

Got any great ideas for objectives, paths, or milestones? Share then on the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group. We’ll be back on Tuesday to talk about making encounters to fill the space between the starting line and the objective.

It’s time to get to the specifics of your first adventure as a GM.

Trail of Cthulhu adventures use a specific format to help you run the mystery smoothly.

- There’s a Hook that tells you how your players get involved in the mystery. In the case of Midnight Sub Rosa, they’re sent to recover the diary of Ezekiel de la Poer.

- There’s a Spine – a set of scenes that you’ll play through as you move through the mystery. Some of these are core scenes, and are required to tell a complete story. Others are alternate or optional scenes. Scenes are linked by

- There’s a Horrible Truth – the revelation of what’s really going on.

- The adventure may include some additional preliminary material – Midnight Sub Rosa, for example, has descriptions of some of the really important Non-Player Characters (NPCs), and notes on presenting the setting of rural Alabama in the 1930s.

- Then, there’s a list of Scenes – the real meat of the adventure. Think of these as scenes in a movie or a stage play, only the script isn’t finished and there’s plenty of room for improvisation and surprises. You’ll set the scene by describing what’s going on (“you’re all in a big country mansion”), and you’ll act out or describe the parts of the NPCs (“Professor Derby greets you warmly, and asks if you had any trouble getting here”), but it’s up to the players to decide what their player characters do.

- At the start of each scene, we list Lead-ins and Lead-Outs. Lead-Ins are scenes that can lead to this one; Lead-Outs are the scenes that likely follow on from this one, depending on which clues the players find with their investigative abilities. You can see an overview of how all of the scenes connect in the Scene Flow Diagram at the start of the adventure.

- Remember the core idea of GUMSHOE – it’s more fun for the players to get lots of clues, and have to work out what they all mean, than it is for them to get only scraps of information and blunder around the dark. Be generous with your clues!

- Investigation is only half the fun, though – it’s a horror game, too! The various scenes have lots of atmospheric details, a selection of eccentric spooky characters for you to play, and monstrous abominations to threaten your players with. When you run the game, you need to build and modulate that atmosphere of horror for your players. Take your time and let them get to know the various NPCs, and let them speculate nervously about what’s going on. Let the tension grow – and then shatter it with a spasm of sudden violence when the ghouls attack!

A Little Reading

Take a look at p. 191 to 203 of Trail of Cthulhu, which is a master-class in building and running adventures, and gives you the tools you’ll need to get the most out of Midnight Sub Rosa.

Read the first 13 pages of Midnight Sub Rosa, and skim the rest of the scenario. Pay attention to the Scene Flow Diagram, so you can see how the various scenes fit together.

A Little Thinking

As you read it, think about the elements discussed in the previous steps—both the fundamental building blocks, and the factors that make an adventure fun and successful. What bits of this adventure appeal to you? Are you more excited about the intrigue and character interactions in the Derby house, or the prospect of chasing around graveyards and examining corpses for clues? Which chills you more – the thought of inhuman monsters like the ghouls, or Irma Derby’s horrific plan to resurrect her mother using forbidden magic?

Maybe you’d like to hop into the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group and talk about the adventure with experienced GMs and other folk, like you, who are exploring GMing for the first time.

And a Little Talking

But that’s not your only activity. As mentioned above, an adventure works best if it plays to the interests and expectations of the players. So have a chat with them. Ask them what they expect and want out of the game. Some players will be happy to go on at length. Others might not really know what they want, or be able to articulate it. In some cases, you may have gamed with the player before, and perhaps already have a good sense of his or her play style. That’s all fine. The goal here is to put yourself in a position in which you can best prepare for a game that everyone will find memorable.

Don’t press your players on this—many gamers don’t really care to think about a game too much before they sit down at the table with a character sheet in front of them. But if you have players who are eager to think ahead about the game to come, then tell them that their characters are part of the Armitage Inquiry, a group associated with Miskatonic University that investigates the occult. What sort of character do they plan on playing? Tweedy professor, two-fisted gumshoe, mysterious occultist, or a socialite with a dark secret?

Alternatively, you may wish to use the pre-generated characters that come with the adventure. These sample player characters are almost ready to go – all the mechanical work is done, but the players will still need to come up with some background details and personality traits. Is Lucia Escobar a stuffy academic or an eccentric parapsychologist who chases after every fringe theory?

Let us know how it goes in the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group, or by tweeting to @NewGmMonth. And talk to you again on Tuesday!

It’s time to get to the specifics of your first adventure as a gamemaster.

“A Rough Landing” the first adventure in the Adventures booklet, was written to be a relatively light-but-flavorful introduction to the world of Glorantha. The world of Glorantha was created by Greg Stafford in the mid-1970s and has been expanded and detailed over the course of 40 years. As such, there’s a daunting amount of information out there about the setting, including the encyclopedic two-volume Guide to Glorantha. But you don’t need to know all that! The first 22 pages of The World of Glorantha booklet cover everything you need, and you really don’t even need to know very much of it to handle an adventure.

Its purpose is to appeal to newcomers and veterans, with a relatively isolated area and new threats, yet connected to existing Gloranthan content. There are no tests requiring extensive knowledge of the background, but players and gamemasters familiar with the setting will instantly grasp the cultures and conflicts being presented.

A Little Reading

Read through “A Rough Landing”. It’s on pages 5 through 23 of the Adventures book of the Starter Set. There’s a short introduction on pages 2–4 about how to gamemaster, what to do when getting ready for play, including a sidebar specifically addressing “first time” gamemasters.

The adventure begins with a simple setup, where the adventurers, weary from the adventure described in the SoloQuest, are arriving in town late at night seeking a place to stay. Unfortunately, they have some bad timing and end up in the middle of a skirmish between some merchants and some (justifiably) angry troll mercenaries!

A Little Thinking

As you read it, think about the elements discussed above—both the fundamental building blocks, and the factors that make an adventure fun and successful. See if you recognize those elements in the adventure. Maybe you’d like to hop into the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group and talk about them with experienced gamemasters and other folk, like you, who are exploring gamemastering for the first time.

And a Little Talking

But that’s not your only activity. As mentioned above, an adventure works best if it plays to the interests and expectations of the players. So have a chat with them. Ask them what they expect and want out of the game. Some players will be happy to go on at length. Others might not really know what they want, or be able to articulate it. In some cases, you may have gamed with the player before, and perhaps already have a good sense of his or her play style. That’s all fine. The goal here is to put yourself in a position in which you can best prepare for a game that everyone will find memorable.

Don’t press your players on this—many gamers don’t really care to think about a game too much before they sit down at the table with a character sheet in front of them. But if you have players who are eager to think ahead about the game to come, you might tell them about Glorantha, described in “Introducing Glorantha” on pages 5–6 of the Adventures book. And, of course, they aren’t limited to talking to you—they’re welcome to discuss their goals with one another beforehand, too.

Let us know how it goes in the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group. And talk to you again on Tuesday!

Pieces of a Mystery

The secret with Monster of the Week, as with most games Powered by the Apocalypse, is that you only need to set up the beginning of a Mystery, and don’t need to worry about where it will end: the Hunters will figure that out for you.

But… how do you set everything up? Every Mystery is broken into four basic parts: the basic concept, the hook, the threats, and the countdown. In our sample adventure, these are already outlined for you. Once you get familiar with how all these concepts interact, you’ll be creating your own Mysteries in no time. Let’s take a quick look at each piece:

Basic Concept: The core premise. In “Dream Away the Time”, the basic concept is that the village has forgotten about their long-standing pact with the King of the Faerie and now he’s sent his forces to punish them.

Hook: The incident or element that draws the Hunters into the Mystery. Handfast suffers a series of strange weather events, a rash of curious attacks, and unusual household mischief. You’ll describe the hook to the Hunters, how they deal with it is up to them.

Threats: These represent anything which could challenge the Hunters. It could be a monster, it could be minions of the monster, even locations and bystanders can present a challenge to the party. (Explaining to an innocent bystander why you’re performing an infernal divining ritual over the corpse of a rapidly-decomposing hell cat is not as easy as you might think.)

Each threat has a motivation which gives you insight as to how the threat will respond to the Hunters’ actions. For instance, Officer Edward Turner’s motivation is “to pass on rumours.” So rather than responding to the Hunters as a gruff, man-of-action, Officer Turner is genial, loquacious, and clearly in over his head.

Countdown: This is what would happen if the hunters never got involved to deal with the situation. The countdown always starts at Day and moves steadily toward Midnight. (These steps are metaphorical, not literal. The names are just intended to give players a sense of things getting worse.) In Dream Away the Time, the countdown starts with Violet and Bonecruncher causing trouble in Handfast. If the Hunters don’t successfully put a stop to events, Bonecruncher eventually eats them or drives them from their homes.

Sections to Read & Review: Creating Your First Mystery (pages 132-147); Introductory Mystery: Dream Away the Time (pages 149-161.)

If You’re Using Roll20

Here is a special treat: the Keeper gets their own mystery sheet, in a sense the adventure is your “character.” To see how it works, create a new character and when selecting the playbook, choose “Keeper’s Mystery Sheet.” You will then see fields for the mystery concept and the hook. Immediately below you will see all the cheat sheets you will ever need: the Hunter Moves Reference, the Keeper’s Reference, and the instructions for using the mystery sheet.

Clicking the +Add button will let you add a new countdown, monster, minion, bystander, location, phenomenon (a new threat type from the Tome of Mysteries supplement), or generic text block for your own notes. Each threat gets its own box where you can add all their information, keeping everything in a single location rather than shuffling between multiple character sheets. To see an example of a completed sheet, Dream Away the Time has its own pre-populated sheet included in the module.

“Adventure.” I guess that’s a word for it.

Here’s what we assigned you last week.

- Primary Objective A: Learn the Delta Green setting (COMPLETE).

- Primary Objective B: Learn the game’s rules by reading Need to Know, pages 5–19 and 33–39.

- Bonus Objective: Watch or listen to actual plays of Delta Green.

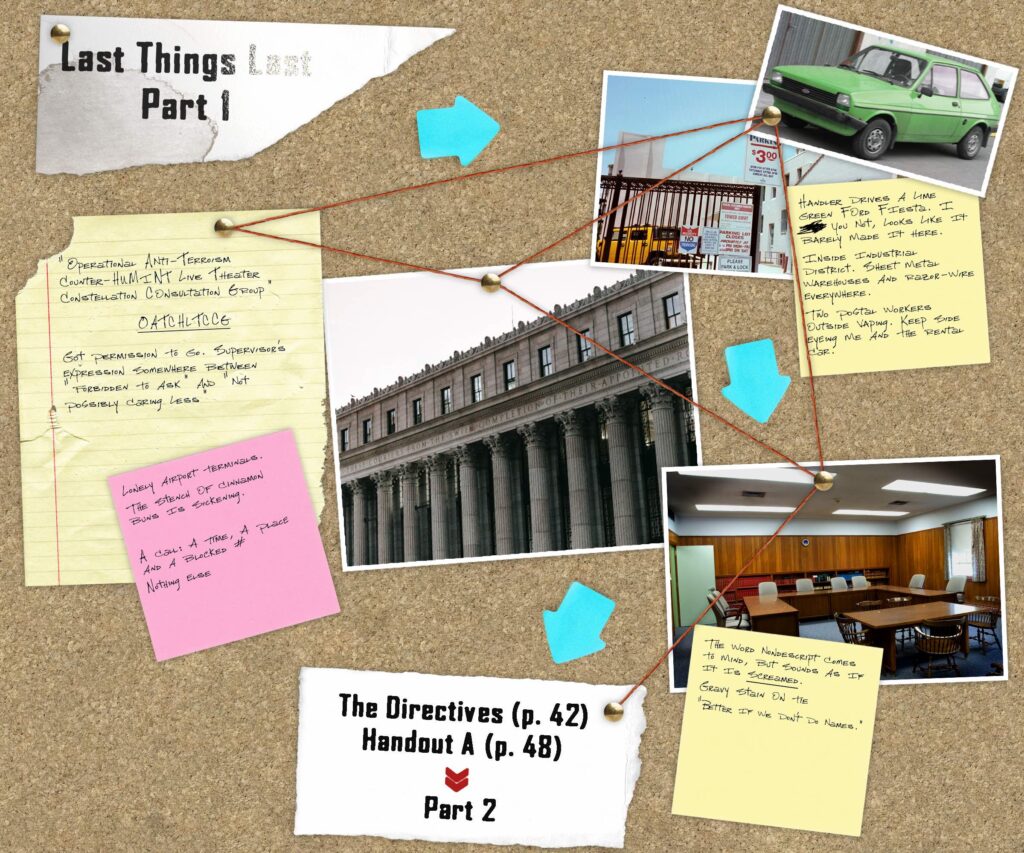

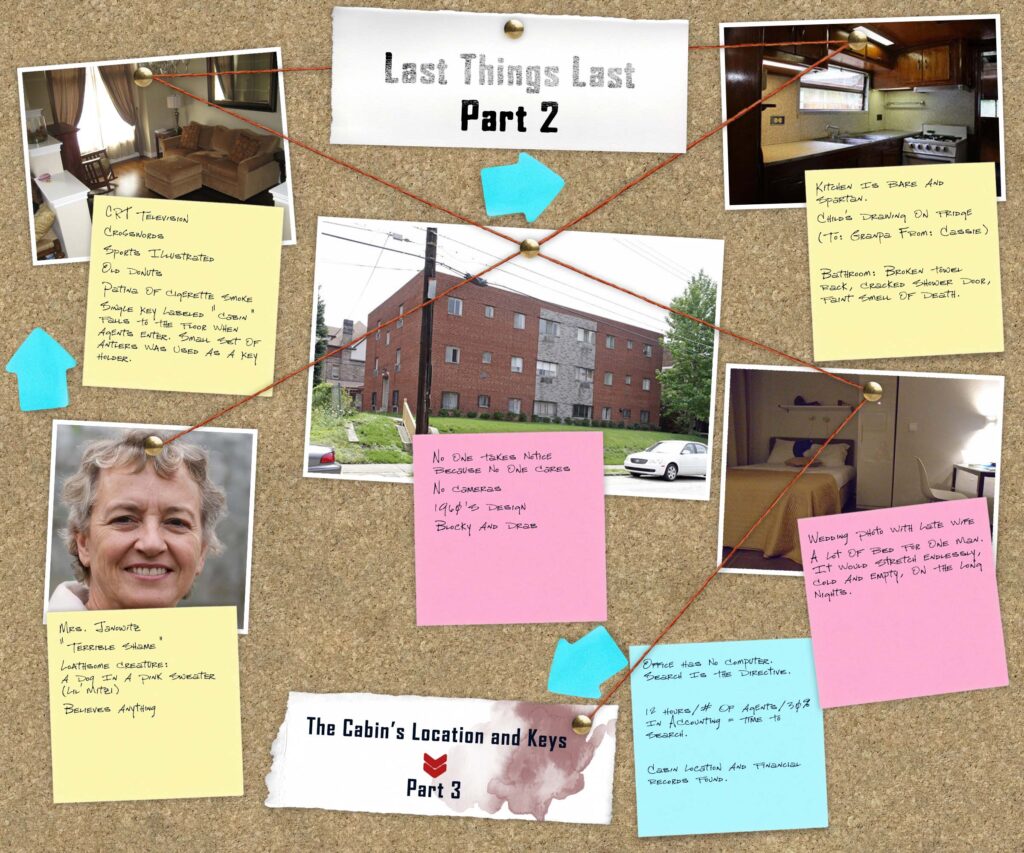

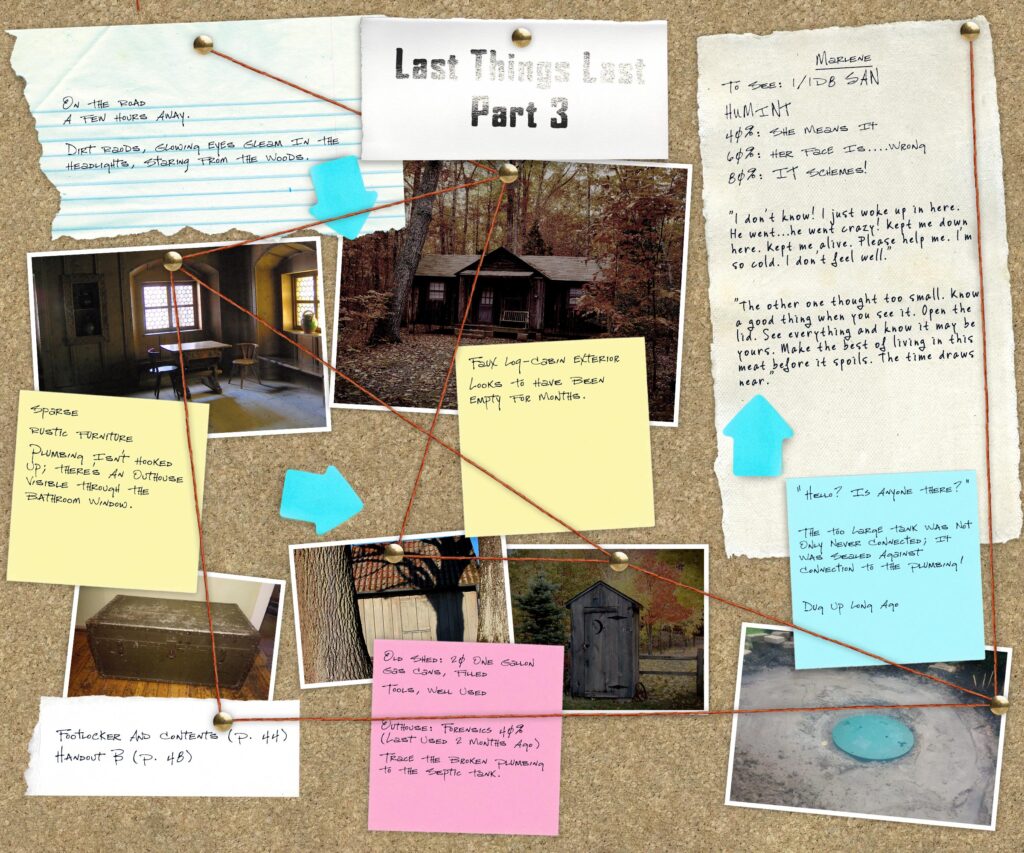

You reviewed the scenario “Last Things Last,” pages 41–48 of Delta Green: Need to Know, in Week One to help inform players about what is coming. Today, we prepare to deploy the scenario at the table.

There Are Only Three Scenes in “Last Things Last”

Things start at the post office briefing. The first part of the investigation happens at Clyde Baughman’s apartment. It ends at his cabin in the woods. In terms of plot, the scenario couldn’t be simpler. It’s very hard for Agents to get off track. Let’s talk about tips that make the game run well.

Delta Green is about mood, so map the mood.

The description of each location in “Last Things Last” is choking with evocative detail. Consider highlighting sections of the text that you can quickly insert into descriptions or use to answer player questions. Write a location name on a piece of scrap paper and surround it with a “cloud” of tags pulled from both the text and your own imagination. For example, I’d write down “Post Office” and surround it with descriptive tags useful for setting the mood, such as, “Handler has deep bags under eyes,” “gravy stain on shirt,” and “MIA/POW keychain.”

But what moody details should you map?

The life of an Agent is about despair; the work of an Agent is about terror.

The literary term for the government side of an Agent’s life might be Kafkaesque. Agents don’t work for Delta Green. That’s volunteer work on the side. They earn their livings as FBI agents or lawyers or doctors or government contractors. They live with the same mundane drudgery as the rest of us, made all the more unbearable by the dark truth of the unnatural.

Delta Green fights an endless war of attrition: an underfunded and illegal mission that daily seems more hopeless and doomed. Above all, Agents must keep their terrible and ultimately criminal actions secret. The boredom and futility of everyday life are punctuated by moments of paranoia.

This drab, pessimistic existence transitions into an atmosphere of existential dread and visceral terror when confronting the unnatural. When you’re talking about past DG jobs or dealing with the thing in the septic tank, the literary influences shift into the Lovecraftian mode: horrors from beyond reason that evoke cosmic terror in the Agents and, in your best moments, the players themselves.

Agents always move forward, with or without the means to survive.

After mapping the three scenes detailed in the scenario and clouding them with mood—briefing, apartment, cabin—draw lines between them and label each line with the vital clue it represents. The briefing (page 41) takes the Agents to the apartment. Someone in the apartment has to find the keys to the cabin or records of its existence (page 42). Once at the cabin, someone has to notice the footlocker and Baughman’s note directing them to the septic tank (page 44).

If you’ve read the scenario, you know that this is only enough information to get into trouble. There’s no reason Agents must be fully equipped to deal with the thing in the tank (page 45) before they meet it. As the Handler, it is your job to take the story from beginning to end. Let the players about whether their Agents survive the trip.

If Agents go off the rails, detour into real life before directing them back to the plot.

Agents sometimes hunt false leads and go to places not outlined in the scenario. Don’t worry. The world of Delta Green is nearly identical to the lived experience of people outside it. If the Agents want to hit up a convenience store for supplies on the way to the cabin, pull descriptions from one you are familiar with. Go for the worst version of a place you can find in your memories. If they want to go to a bar, make it the seediest one you’ve ever seen. If it’s a rest stop, describe the toilets broken and overflowing. Use these diversions to maintain the mood. Then remind players of the mission objectives to get them back on track.

You know what? Just let me draw that map.

It may make a useful example. I can be…kind of a control freak about the details. You’ll get that way about the small stuff, too.

If you make it that long.

Welcome to Session 4 of New Gamemaster Month for the Tales of the Valiant roleplaying game! Last time, we talked about rules. This time, let’s focus on storytelling.

Last week, we chose an adventure for your first session. We decided on Kobold Press’s fan favorite, The Impregnable Fortress of Dib, to provide a smooth introduction for both the GM and players.

If you haven’t downloaded a copy yet, get it for FREE using the link below.

As you embark on your first adventure as a game master (GM), pay attention to three key elements:

The Story

The Impregnable Fortress of Dib is designed as a straightforward, three-page adventure. This format provides enough building blocks for the structure while allowing you the freedom to create a story that responds to what the players do. To fully grasp the story, be sure to read the entire adventure first.

- Open the PDF and read the Introduction on page 3.

- Read the complete adventure from pages 4–6.

Note: You do not need to read the second adventure, Dib’s Wagon of Doom. You can stop at page 6!

The Structure

As you read through the adventure, consider the elements that contribute to its enjoyment and what will make it successful in gameplay. Your GM notes might cover the following points:

- What is the beginning, middle, and end of the story?

- Identify the who, what, when, where, and why based on the text.

- Where can you incorporate your own unique bits, and how can you engage the characters effectively?

Look for these elements as you read the adventure. You might also want to join the Kobold Press Discord to discuss your insights with experienced GMs and others who are exploring GMing for the first time.

The Players

An adventure is most effective when it aligns with the interests and expectations of the players. This is the perfect opportunity to talk with them about what they expect and hope to experience in the game. Some players may share their thoughts at length, while others might struggle to express their preferences. Both are good starts!

This is also a great time to discuss scheduling a session 0, where you can build characters, establish safety tools, and clarify expectations before gaming. Kobold Press recommends using the Deck of Player Safety to implement accessible safety tools at your table.

If you’ve gamed with some players before, you might already have a sense of their play styles. Regardless, your goal is to prepare for a game that everyone will find memorable.

It’s perfectly fine if your players don’t have answers to your questions right away. Many gamers prefer to dive in without overthinking it until they sit down with a character sheet in hand. However, if you have players who are excited to think ahead, consider finding a personal character hook or other reasons to help them engage with the adventure.

Remember, players aren’t limited to discussing their ideas solely with the GM; they should feel encouraged to collaborate with each other as well. They might discover an adventure hook that fits the entire party better than just a single character’s perspective.

We’d love to hear about your experiences in the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group. We’ll be back on Tuesday to discuss encounters!

Blood on the Range (pages 7-8) assumes that the characters are already riding together as a posse in Wyoming. They’ve heard about a $100 reward for finding a killer, and ride to Heath Crittenden’s ranch to investigate. After setting that scene, there’s a block of text for the GM to read out loud that sets a few important details, including the presence of a Ute war party nearby.

🕵️♂️ The Crime Scene

The proper adventure starts here, and the Survival rolls make a good introduction to Trait rolls. Anything else the characters try might lead to the same results: blood on the barbed wire and a total absence of other tracks. Once any investigations wrap up there’s two main directions the posse can go: out beyond the wire to question the Utes, or back to the ranch to investigate Hank’s body. If the players seem unsure, have Crittenden prompt them to track the Utes. They seem to him like the main threat. Once the posse returns to report what they find they can get a look at the body.

Alternatively, if the posse are keen on examining the body right away they can. Once they finish investigating, Crittenden can ask them to check along the boundaries (leading to the encounter with the Utes) or jump directly to the final encounter: Blood on the Wire.

Let the posse poke around, question cowhands, or whatever they think up. If you aren’t sure how to handle something, trigger Blood on the Wire. You can roll into that encounter whenever and wherever you need to, and so it’s always an option if things get stuck. The finale is an Encounter, so for a few words of advice about those next time!

Throughout this program, we have expert GMs on hand to answer questions and provide general support at the New Gamemaster Month Discord Server or the New Gamemaster Month Facebook group. Please drop in, join the group, introduce yourself, and ask any questions you might have. Other new GMs will also be there—it’s a great place to share your experiences and support one another. Hope to see you there!

Pingback: Routinely Itemised: RPGs #292